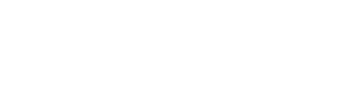

Herbert Martin was born on March 6—the same day as Michelangelo. And, like the famed painter, sculptor, architect, and poet, he has mastered any skill or trade that caught his eye.

“Some people call me a ‘Renaissance man,’” Herbert admits. “I don’t know if that’s true or not.”

Over the course of his life, the African American architectural designer advanced through firms during a time when few employers hired black professionals. He later wrote classroom curriculum and taught school in Kentucky, and then, he became an inventor and children’s book author—because the quiet life of retirement didn’t suit his restless ways.

Throughout that time, Herbert acted an advocate and mentor for young African Americans, inspiring them to reach their full potential and helping them find jobs in the architectural field.

A simple beginning

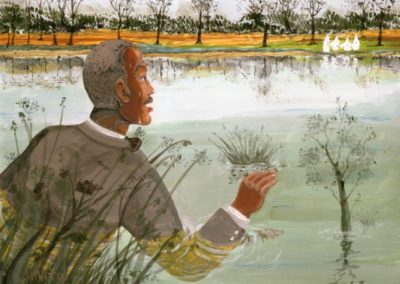

Herbert’s story begins in Cairo, IL, where he grew up during the 1940s and ‘50s. The young man learned the value of hard work from his father, Samuel Martin. After high school, Herbert got his first job in construction by working on a ditch and out-digging another applicant.

“My dad told me then … that if there’s one job to be done, and there are five people standing around to do the job, you make sure you’re the one doing the job,” he says. “I kept that in my mind.”

Herbert spent two years at the company, learning all he could from his coworkers and living his days surrounded by the creativity and excitement associated with any new building. It inspired him—and his father. Samuel decided that his son would work for Epstein, a design and construction company in Chicago.

“I said, ‘Dad … they haven’t hired a black,’” Herbert remembers. “And, he drove me over to Epstein’s. He parked the car and said, ‘Go in there and get a job.’”

Half an hour later, Herbert says, he had snagged a position.

Epstein hired him as a designer and illustrator in 1961, even though Herbert had no formal degree. He had only taken high school drafting classes and a few college courses. He also says the firm employed more than 300 engineers and architects, but he was the first African American on staff.

The ambitious young man worked for two other Chicago architectural firms over the next eight years, slowly proving his chops as a building designer. During that time, he got married, and in 1969, his wife found a teaching job in Paducah. So, Herbert also got a teaching job in the city—at Paducah Tilghman Vocational School.

A New Direction

Over the next 29 years, Herbert taught drafting, engineering, and design at the Kentucky State University, West Kentucky Technical College, and Paducah Community College. And, by 1974, he had earned a bachelor’s degree in education and a master’s degree in vocational administration from the Murray State University. He even spent some of that time traveling the state for the University of Kentucky, educating other teachers on the art of writing classroom curriculum.

Herbert had found a new passion.

“I’m most grateful for the good that I did in teaching because I’ve had students tell me that I was the best teacher that they ever had,” he says.

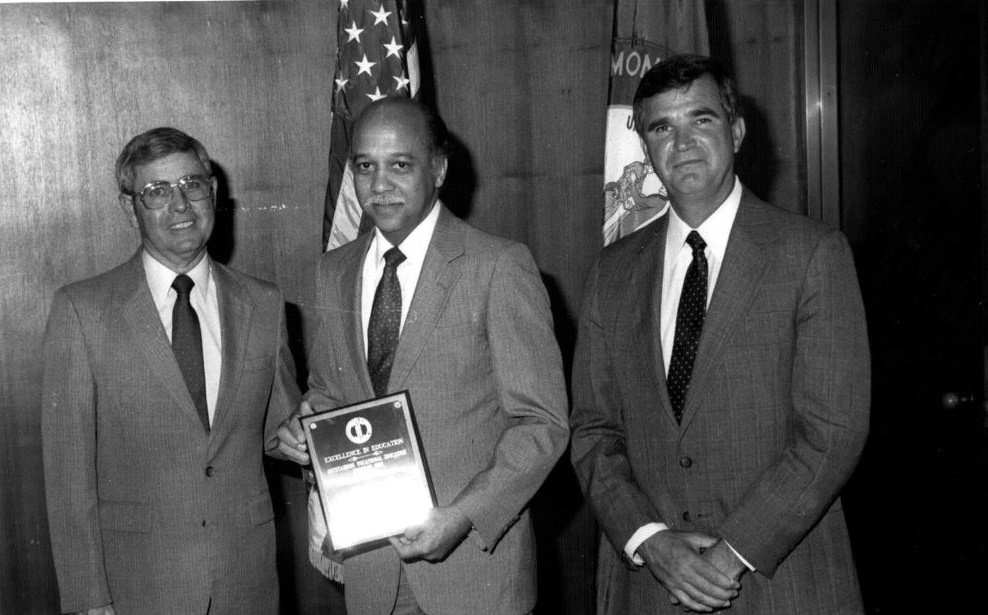

During the course of his career, Herbert says, he was voted Most Outstanding Teacher at West Kentucky Technical College, and his architectural drafting program was named the 1988 Most Outstanding Program in the state.

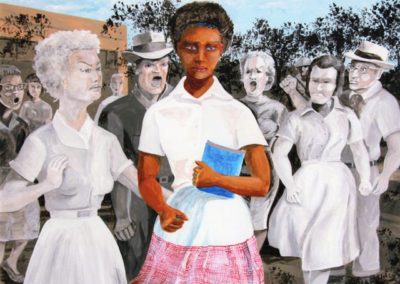

However, Herbert considered his greatest achievement the fact that he could give students—particularly African American students—the knowledge they needed to find jobs. In 1982, he successfully applied for a grant to study a digital drafting program in Milwaukee, WI, and then install it on ten computers at West Kentucky Technical College, a predominantly black school.

It was the first grant the school had received for a vocational technology program, and the skills Herbert’s students learned on those screens helped them find employment with ease.

“Everything was moving so rapidly at that time,” he explains. “Everyone wanted to draw on computers.”

In 1994, Herbert also helped design a monument to D.H. Anderson, the founder of West Kentucky Technical College. At the time, the school was making plans to merge with Paducah Community College and form what is now West Kentucky Community and Technical College (WKCTC). Herbert wanted to preserve the institution’s African American heritage, so he suggested honoring Anderson’s memory at the entrance of the D.H. Anderson Technical Building on new WKCTC campus. The monument’s black, reflective rock bears Anderson’s portrait along with the image of a lantern.

“From this light rode forth an educational vision that still shines brightly today,” the inscription reads. “Anderson believed that education and job training were vital for change for African Americans.”

And, so does Herbert.

A Not-So-Final Ending

The ambitious teacher retired in 1998, just a few years after designing Anderson’s monument. Yet, he has never slowed down.

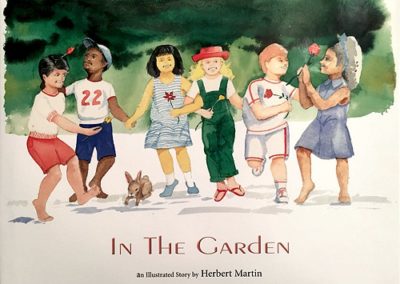

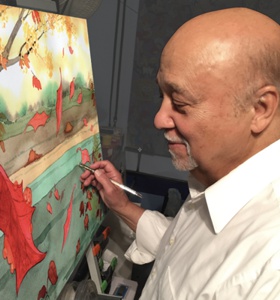

Since his last day in the classroom, the talented man has published three children’s books and has applied for patents on multiple inventions. At the moment, he says he’s collaborating with author Patricia McKissack on a book about unsung heroes (one of which is D.H. Anderson) and working on two devices that he believes could help reverse global warming.

After nearly six decades of designing and teaching, imagination still flows through Herbert. He can’t stop dreaming and creating. He can’t quit working.

He’s a Renaissance man—and he still has skills to master and lives to impact.